Khajistan is rescuing and digitizing overlooked histories from the Islamicate world.

BOOKSHOP

KHAJISTAN PRESS

Price:

from $12.00

from $12.00

Loading…

Price:

from $2.00

from $2.00

Loading…

Price:

from $2.00

from $2.00

Loading…

Price:

from $38.00

from $38.00

Loading…

Price:

from $6.00

from $6.00

Loading…

Price:

from $6.00

from $6.00

Loading…

Price:

from $6.00

from $6.00

Loading…

MERCH

-

Read more: Khajistan Manifesto / 2025

Khajistan Manifesto / 2025

by Saad Khan

Khajistan archives banned and overlooked media from Indus to Maghreb. We preserve real life that somehow disappears from the official record. We d...Read more -

Read more: Kharabat Vol. 1 Launches in London, Paris & NYC

Kharabat Vol. 1 Launches in London, Paris & NYC

by Khajistan Cultural Desk

Khajistan Press invites you to the launch of Kharabat Vol. 1 at Reference Point, London; Noosh Bar, Paris; Storm Books & Candy, NYC; and Printe...Read more -

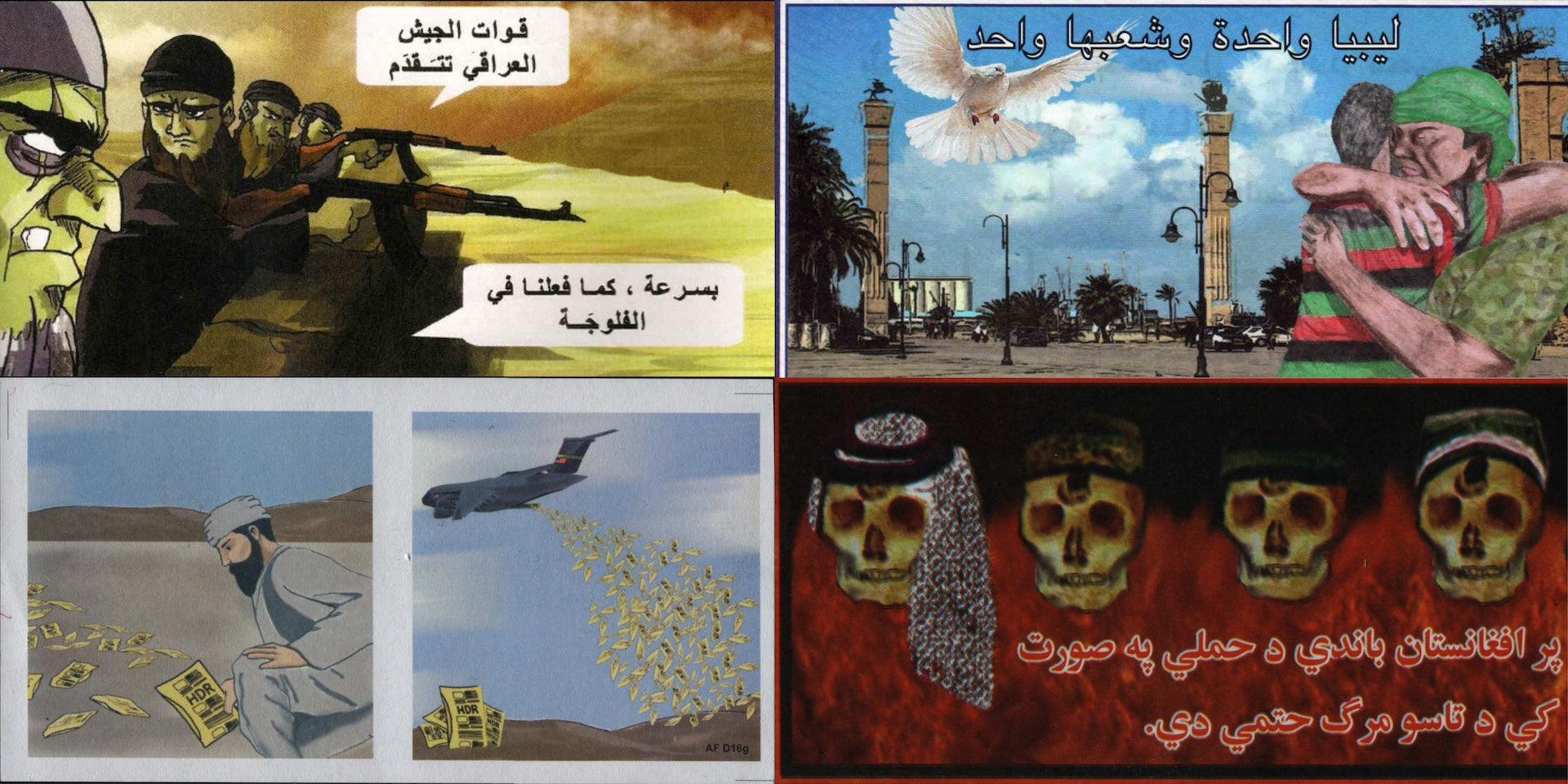

Read more: Book Launch: American War Propaganda Leaflets: 1990–2022 by Khajistan Press at Printed Matter, NYC

Book Launch: American War Propaganda Leaflets: 1990–2022 by Khajistan Press at Printed Matter, NYC

by Khajistan Cultural Desk

Launch + conversationWhen: March 13, 2024, 6–8PMWhere: Printed Matter, Inc., New York CityJoin us at Printed Matter for the launch of American War ...Read more -

Read more: The Paper Trail of War: American War Propaganda Leaflets by Khajistan Press

The Paper Trail of War: American War Propaganda Leaflets by Khajistan Press

by Harris Gondal

"The Paper Trail of War: A Review of American War Propaganda Leaflets by Khajistan Press" unveils the covert yet powerful role of psychological warfare in shaping modern conflicts. From blood-stained Iraqi flags bearing haunting caricatures of Saddam Hussein to promises of peace superimposed over scenes of destruction, this collection lays bare the intricacies of U.S. psyops during The Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and beyond.Read more